A toxic culture can often be the culprit behind issues or scandals faced by companies. A “healthy culture really is the strongest control, but a toxic one is the greatest risk,” said Richard Chambers, senior risk & audit advisor at audit and compliance platform AuditBoard.

However, creating an effective strategy to ward off cultural risk can be easier said than done for many companies: while 80% of governance, risk and compliance professionals agreed organizational culture is important, who takes responsibility for managing that risk is often more nebulous, AuditBoard found in a recent report.

CFOs are in a key position to take ownership of such risks, as, in many companies, departments such as risk management and internal audit often report in to the finance chief, Chambers said. It’s crucial, therefore, for finance chiefs to be “cognizant of the risks around culture,” he said.

“[CFOs have] got tremendous responsibilities in helping the CEO and the C-suite and even the board, giving them the kind of accurate and reliable information they need to be able to make decisions, that I think a lot of times they don't necessarily connect the dots when it comes to, ‘what are the financial implications of a toxic culture?’” he said in an interview Wednesday.

Hedging against cultural risks

For Chambers, culture can be boiled down simply to, “how things are done around here,” he said, “That's not original…but it really is, what are the behaviors that often characterize a company?” However, that doesn’t mean culture is one-size-fits all: business cultural mores can change across geographic regions or from department to department.

“You may have a tone at the top that's set by the CEO and others in the C-suite at corporate headquarters, but then when you start looking at the different business units, you may find that maybe they're not subscribing to what the tone at the top would indicate that they ought to be,” Chambers said.

Bringing that understanding of culture into one’s risk management strategy is essential to accurately track risks and to guard against the development of a toxic culture: “I always advise internal audit to start looking at culture in every audit that they do, because culture will often be the root cause of problems that they find,” he said.

However, “I think it's a mistake a lot of times for oversight functions, whether it's audit risk or compliance, to try and take on the whole organization, the whole enterprise, right out of the gate,” Chambers said.

In a 2023 study, AuditBoard identified internal audit as a critical part of cultural oversight, but “our 2025 findings show that internal audit alone cannot shoulder assurance on culture risk,” its 2025 Organizational Culture and Ethics Report found.

“Culture risk is now tied to some of the most dynamic and sensitive risk areas organizations face, like AI ethics, ESG authenticity, hybrid work norms, and shifting political expectations around DEI,” the report reads, noting if business leaders don’t align on a clear strategy for managing such risks, they can fall “out of step with regulators, employees, and stakeholders, not to mention opportunities for performance gains that are lost.”

There’s a “clear, bright line” between healthy culture and long-term business performance, Chambers told CFO Dive in a 2023 interview regarding the previous study.

“You can have a great business strategy,” he said Wednesday. “We can have a vision, a destination, where we want to take this company. But I think culture is often the wind, and it can take you far off course, if it's not closely monitored and adjusted when it’s getting toxic.”

Putting the CFO at the cultural helm

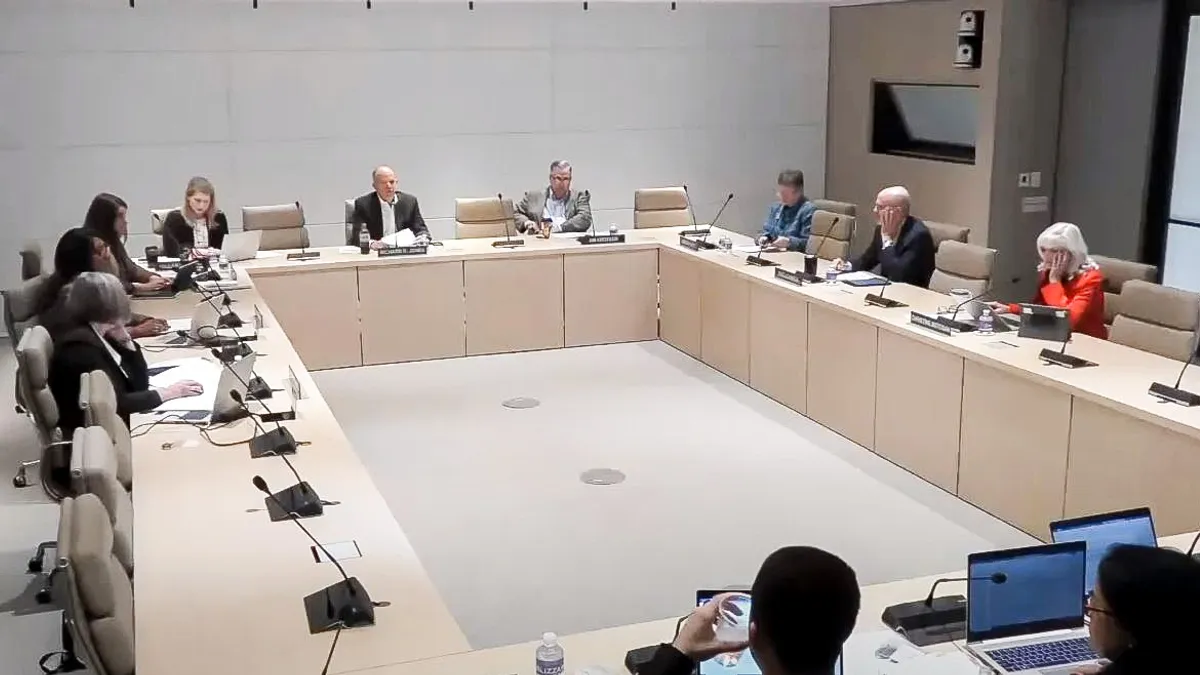

As businesses look to juggle an ever-increasing set of risks, many are asking their CFOs to chart a clear path through both macroeconomic and internal challenges, including cultural risk. For the CFO to do so, however, they need to be able to see the whole picture, which can be tricky when disparate parts of the business tackle risk in siloes, with their own technology solutions.

If compliance, risk management and internal audit are all examining risks themselves, and “if their technologies don't talk to each other, there's no sort of single source of truth,” Chambers said. The finance chief can play a critical role when it comes to bridging these gaps, he said.

“That's where I think CFOs need to keep their eye on the ball and make sure that these key players, many of whom are direct reports to the CFO, have the technologies and the resources they need,” he said. Finance chiefs should also be “setting the expectation” for greater collaboration and communication between these previously siloed teams and systems, he said.

However, Chambers would advise CFOs against attempting to manage that technology themselves, but rather to “enable the key players in the…so-called silos, if you will, to identify and acquire the kind of cross functional technology solutions that they need,” he said.