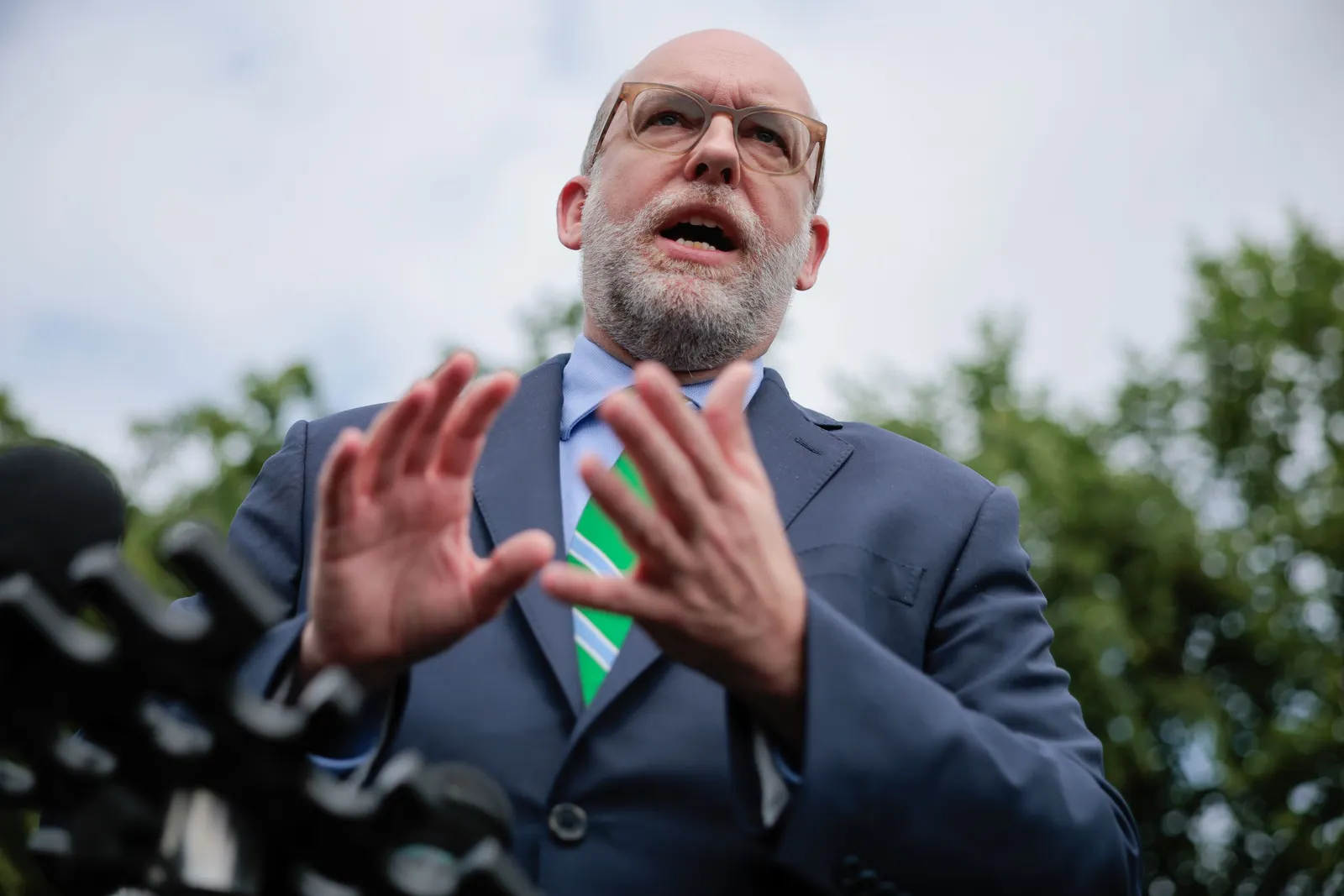

When David Silberman first contemplated a new service called “earned wage access” as a regulator at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2011, the issue had religious overtones for him.

He couldn’t help but think that giving workers access to their pay more immediately after they had earned it made sense. Why should they wait for a payday in the digital era?

“My initial reaction was, the Bible says to pay workers at the end of the day, because it's their wages and they need it,” Silberman said, noting it was his personal opinion, not that of the agency. While that may have been an antiquated perspective, so was a two-week pay cycle.

“Being paid bi-weekly is an artifice of an analog era,” Silberman said during an interview last month, looking back at the concept he encountered circa 2011 as an associate director at the agency. “If technology made it possible for people to get their wages as they earned it, that seemed like a fairer world.”

Venture capitalists, including big names like Andreessen Horowitz and General Atlantic, have wagered that others will agree. Such investment firms have injected upwards of $3.5 billion over the past decade in companies that offer software tools to digitally disburse payments to workers before scheduled paydays, according to the Morningstar research firm PitchBook.

Dozens of such companies, called earned wage access providers, have sprung up in the U.S., pitching their services as a way for workers to tap their earned pay early, via employers or online. Backers of EWA services, which are typically delivered to workers through a phone app, contend they are a cost-effective alternative to usurious payday loans.

The Associated Press last year delved into how earned wage access users, such as Anna Branch of Chattanooga, Tennessee, are tapping such services to cover expenses.

The restaurant chain McDonald’s, ride-share company Uber Technologies and retail giant Walmart are among the employers offering such services to workers. Those companies declined to comment or didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“Across the country, millions of consumers are utilizing safe earned wage access as a viable alternative to high-interest lending products,” said Phil Goldfeder, who leads the American Fintech Council. “Consumers are turning to earn wage access as an alternative. We need to find ways to encourage that, and build a regulatory structure that makes the most sense,” he said in an August interview. The AFC is a trade group in Washington whose members include EWA providers.

But consumer advocates view most EWA providers as profiteers taking advantage of low-wage workers in a largely unregulated market. The workers can too easily be duped into paying excessive fees and leaving tips for EWA agents they’ve never met, accumulating unwieldy debt along the way, the advocates argue.

How to regulate the industry has become a controversial issue, especially following a Trump administration retreat from fintech oversight. Under the Biden administration, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau aimed to increase regulation for EWA providers, but now states are grappling with how to step in.

The CFPB pullback is “a bit of a double-edged sword,” says Frank Dombroski, CEO of earned wage access provider FlexWage Solutions. On the one hand, it gives EWA providers like his a green light to grow, but on the other hand, it creates “uncertainty in the marketplace and in the minds of the employers,” he says.

Chopra attempts to rein in EWA

Last year, the CFPB issued an interpretive rule that imposed a major stipulation on EWA providers, “many” of their payouts would be considered loans and subject to lending laws. That directive under Biden’s CFPB director, Rohit Chopra, drew a barrage of protest from earned wage access providers.

Chopra’s approach was an about-face from the first Trump administration, which had begun to develop policies that were less restrictive. In November 2020, the CFPB issued an advisory opinion that determined that certain earned wage access offered through employers without fees wouldn’t be considered loans.

The following month, the agency carved out a safe harbor “sandbox approval order” for a major company in the industry, San Jose, California-based Payactiv, saying it wouldn’t be liable under lending laws. But that leeway for Payactiv was eliminated under Chopra in 2022.

Now, the Trump administration is shifting gears again, with its shrunken CFPB, under Acting Director Russell Vought, issuing an April memo that said it would “deprioritize” oversight of digital payments. This month, Vought said he’s planning to shutter the agency.

“We went from having nothing to having something, to having something different, back to having nothing, so it's been quite the evolution,” says Joseph Schuster, an attorney at the law firm Ballard Spahr who represents clients in the young industry. States and courts are entering the fray now, he noted in an interview last month.

EWA industry mushrooms

Earned wage access, sometimes called on-demand pay, comes in a variety of forms for workers, sometimes offered by employers, but also directly to workers.

FlexWage and Payactiv offer services through employers. While FlexWage charges workers fees for EWA transfers that vary by employer, Payactiv puts workers’ wages on debit cards that generate income from merchants paying interchange fees when employees spend with the cards.

Tampa-based Branch provides EWA card services to Uber drivers, who are contractors as opposed to employees. “The core of our product was always a digital wallet, so think of it as a payment rail where we can send money any day, day or night, for free,” CEO and founder Atif Siddiqi said in an August interview.

But some EWA providers have taken a different tack. They also pitch their services as free, but offer them directly to workers, leap-frogging employers. They charge workers fees to expedite payments and encourage them to leave tips that bolster revenue.

Workers can tap the services directly from providers, such as Dave or Activehours, which does business as EarnIn. How it typically works is the companies get workers’ permission to access their financial accounts, and then monitor hours worked and direct deposits from employers.

FlexWage's typical fee is $3 per transfer, with a cap of $6 per pay period, for disbursements within seconds. EarnIn offers free transfers within one to two business days, but charges between $2.99 and $5.99, depending on the transfer amount, for delivery within minutes.

“Consumers want the product,” EarnIn CEO Ram Palaniappan said in an August interview. “The consumer advocates are not on the same page as the consumers.”

Additional competitors in the arena include DailyPay, Clair and TapCheck. Meanwhile, some neobanks, including Chime, and other fintechs, such as Gusto, offer EWA as part of a broader suite of financial services.

When EWA services first emerged some 15 years ago, there was a notion employers might cover the cost of the services for employees, but that didn’t happen. Competition among EWA providers became so intense they jockeyed to attract clients by eliminating costs to the employers.

Big public companies have been drawn to EWA services because it offers an edge in the competition for workers.

Some McDonald’s locations have turned to Tapcheck or DailyPay to provide earned wage access services, according to the EWA providers. Meanwhile, Walmart relies on OnePay, a fintech that it invested in.

The temporary staffing business Indeed Flex, a unit of the British talent search firm, uses Branch to provide EWA services to workers. The EWA market is “probably more competitive now than it was two years ago or so, when we first started working with Branch,” said James Terry, Indeed Flex’s head of revenue.

But it's still “definitely something that separates us from the rest of the pack,” Terry said in an interview last month.

Consumer advocates assail EWA

Nonetheless, consumer advocates are alarmed by the burgeoning industry’s practices, and the lack of government oversight. Organizations such as the National Consumer Law Center and the Center for Responsible Lending consider EWA providers to be a new form of payday lending that charges excessive fees and traps low-income workers in a cycle of debt.

“These companies are manipulating people into incurring costs that are far higher than appears,” says Lauren Saunders, the National Consumer Law Center’s director of federal advocacy. “These companies are pushing people to take out smaller and smaller loans, but more and more loans.”

When the General Accounting Office issued a report on the earned wage access trend in March 2023, it found EWA more economical than payday lending, but noted other shortcomings, including a lack of transparency about costs, user dependence and inaccurate wage estimates.

The direct-to-consumer business models presented particular problems if income data was faulty, the GAO said, noting one EWA provider used GPS readings to track worker hours at an employer’s address. “If wages are inaccurately estimated, consumers may have difficulty repaying the amount they receive,” the report said.

The payday lending comparison sets a very low bar for evaluating EWA, Saunders argued in an August interview. Tiny fees paid by workers multiply quickly to the benefit of EWA providers and to the detriment of workers, she said. “What feels like relief today, because I get some credit, puts me in a bind next week because I can't pay my bills, because my paycheck is depleted, and then I fall into this cycle,” she said.

To illustrate the pitfall, Saunders points to a lawsuit New York Attorney General Letitia James lodged against DailyPay in April that alleged one worker received 450 payouts from an EWA provider in less than two years and paid $1,400 for the privilege. The AG labeled the disbursements by DailyPay, and another EWA provider that was sued at the same time, MoneyLion, as “illegal high-interest loans.”

Likewise, consumer advocates have taken on industry representatives at the federal and state government levels, seeking to persuade lawmakers that EWA providers and their services should be reined in.

The Center for Responsible Lending disseminates research to local organizations to lobby state legislators on the issue, arguing that heavy EWA use leads workers to stack loans, sometimes across multiple EWA services, and to incur overdraft fees on other accounts when they can’t pay bills.

About a third of borrowers tended to reborrow via the EWA services within two weeks, and about a quarter of users accessed advances 25 or more times per year, according to a CRL report last October.

That amounts to a cycle of repetitive, day-to-day use that isn’t free, and isn’t for emergencies, says Monica Burks, a policy counsel for CRL at the state level on the issue. “Our biggest mission is to educate lawmakers to help them see that earned wage access is not a payment solution – it’s a lending product, and it has to be regulated as such to stop this industry from overreaching and really just draining the low- to moderate-income workers’ pay,” Burks said in an August interview.

Industry trade groups have published their own research highlighting EWA benefits, and have criticized the consumer advocates’ reports as “flawed.”

Burks called the loss of the CFPB’s leadership on the issue “devastating” because the agency was a credible source of EWA data and it set the tone for states, many of which are weighing how to regulate the industry.

About half of state legislatures have considered EWA proposals since 2023, according to the American Fintech Council, and the debates are expected to continue next year.

States become battlegrounds

The American Fintech Council has been on the frontlines of battles over EWA since it was formed in 2021, the year that the Biden administration’s CFPB began to explore how to regulate the growing industry.

Now, Goldfeder is crisscrossing the country to protect EWA providers’ interests, lobbying state legislators on industry-friendly bills. He’s a former New York legislator who also worked for a financial institution, Cross River Bank, that partnered with fintechs.

About a dozen states have enacted earned wage access laws. Nevada was the first state to pass a law in June 2023, establishing an EWA licensing process for providers. The law won support from a Democrat-controlled legislature and a Republican governor.

Other states followed suit with Missouri enacting a law in 2023, followed by Wisconsin, Kansas and South Carolina last year, and Arkansas, Indiana, Utah, Maryland, Connecticut and Louisiana this year.

Most of the laws require EWA providers to register with a state and pay a fee, but there are few restrictions. Importantly, these state laws avoid labeling EWA services as a loan, and therefore don’t make them subject to lending laws.

But some states have taken a stricter tack. Last year, California’s Department of Financial Protection and Innovation finalized regulations that took effect this year, making EWA services subject to the state’s existing lending laws, with exceptions for those provided through employers.

The rule “allows for EWA providers to be part of the California ecosystem, serving California users, while also making sure that they are examined and that there are protections that users have and that the state regulator can engage with these providers,” said Avy Mallik, who helped shape the state’s policy as DFPI’s general counsel. “It's working in a way where, frankly, it’s serving everybody, and that there aren’t any misleading fees, or things of that nature,” said Mallik, who left state government to join the law firm Morrison Foerster this month.

More state lawmakers are questioning the business. The Connecticut and Maryland laws took a harder line this year, instituting fee caps in the former and mandating “reasonable” no-cost options in the latter.

Many other state legislatures have considered earned wage access bills, but dissension has often stymied action.

Fighting the well-resourced industry in state capitals to win stricter EWA regulations isn’t easy, consumer advocates say. “These companies have millions and millions of dollars to spend on lobbying that consumer protection groups can’t possibly match,” Saunders said.

Asked about the cost of the American Fintech Council’s state campaign, Goldfeder declined to say how much the trade group is spending.

To be sure, the council’s members aren’t eager to adhere to 50 different state policies. “We always prefer a national regulatory structure,” Goldfeder says. ”However, in the absence of clarity from Washington, we’ll work with every state in the country to create appropriate regulatory structure.”

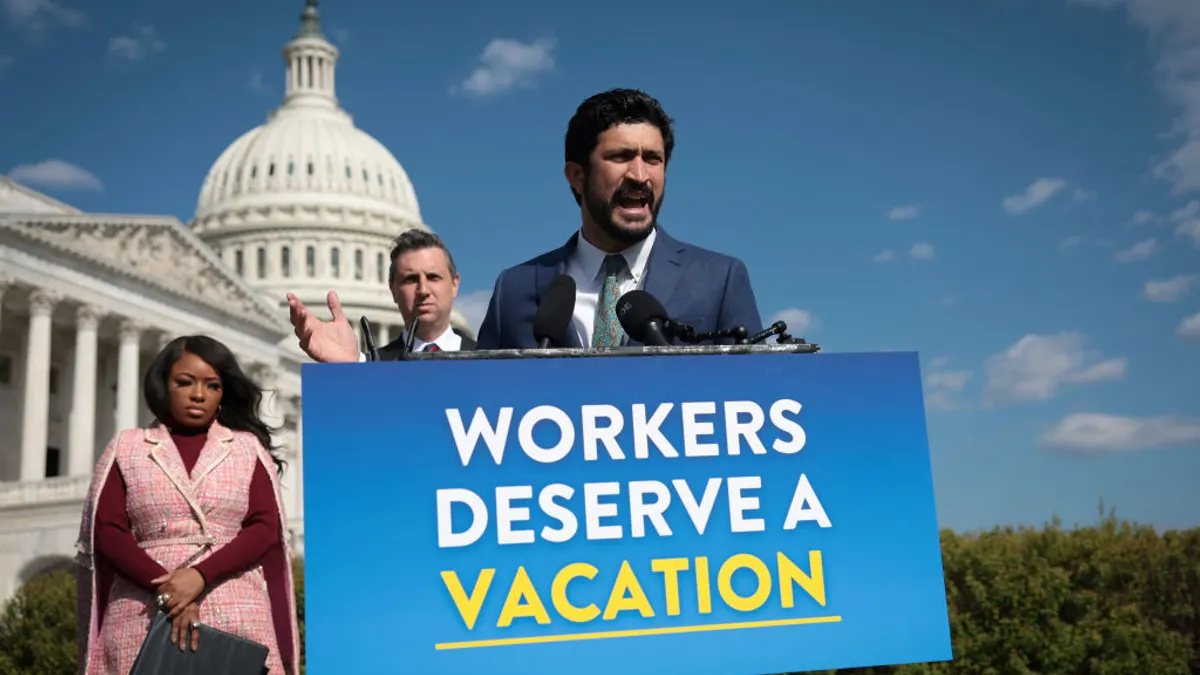

The council continues to encourage Republican U.S. Rep. Bryan Steil, of Wisconsin, to reintroduce EWA legislation he offered in Congress last year, but so far, no luck.

EWA executives splinter

Executives leading EWA providers aren’t in agreement on regulation either. They’ve splintered in their conversations with regulators, casting some rivals as problems.

Some of those providing services through employers view the direct-to-consumer providers as having tarnished the industry’s image.

Scottsdale, Arizona-based FlexWage is one provider that hasn’t joined the American Fintech Council. None of its clients pay fees for expediting payments, stresses Dombroski, who founded the company.

Even in states that require no-fee options, some EWA providers impose ancillary fees to move pay from a digital wallet to accounts, he explained in an interview last month. It subjects workers to “deceptive practices and just unbridled fees,” he said.

“They're kind of high-tech payday lenders,” Dombroski said of some competitors. “They’ve been trying to hitch their wagon to the earned wage access nomenclature to avoid regulation.” He also says “they’ve been very aggressive at promoting very weak legislation.”

FlexWage won exemptions to the lending laws in California and Connecticut by demonstrating to regulators that its disbursements through employers are not loans.

Dombroski was encouraged recently that a federal court in Maryland called out EarnIn’s practices as lending in a case brought by consumers. “We think that really does open the door for a lot of the states who have enacted that kind of loose regulation to now determine what is earned wage access versus what’s lending,” Dombroski said.

And that’s not the only legal challenge that EarnIn faces. It’s being sued by consumer plaintiffs in California and Pennsylvania making similar claims and seeking class action status. The company was also sued by District of Columbia Attorney General Brian L. Schwalb, whose office alleged last November that the EWA provider used false advertising, poorly disclosed its fees and operated without a lending license.

Strategies shift

As the pressures mount, some EWA providers are adjusting their businesses.

For instance, Palo Alto, California-based EarnIn in July rolled out a kind of real-time service that makes pay available to workers as they earn it. Palaniappan says it’s “a very different product from EWA…reimagining, to a greater degree, how payroll can work.”

Also, EWA provider Tapcheck’s CEO, Ron Gaver, said in June that the company increasingly seeks to integrate its software with human resources service providers, signing up with behemoth Workday. Payactiv also hooked up with Workday the following month.

DailyPay’s leadership has been in flux, with the company this month installing its third CEO in less than two years, naming its executive chairman, Nelson Chai, to the post. His appointment comes “as DailyPay’s strategy has advanced to encompass employee financial wellness,” the Oct. 1 press release announcing his selection said.

States take the lead

To guide their corporate strategies, earned wage access providers seek increased regulatory clarity. They may have to turn to the states. “California has provided a pathway — maybe other states will emulate it,” Mallik said.

Companies should watch state as much as federal regulatory moves, counsels Mallik, who was also formerly director of fintech policy for the House Financial Services Committee in Washington. “It is a dynamic time, and I think that states will continue to lead the charge,” he said.

For Silberman, the former CFPB official who wrestled with EWA for nearly a decade at the federal agency, some EWA services have evolved into “a short-term, small-dollar loan.” While he considers EWA services generally preferable to predatory lending alternatives, he worries workers may stack EWA loans in an unhelpful way.

Fees have increased and tips are “problematic,” he said. Looking ahead, with federal oversight in flux, he predicts EWA services may not be viable under state usury laws that cap interest rates on loans.