The Trump administration's opposition to a proposed 15% global minimum tax and its demand that countries by year-end exempt U.S firms from the tax have injected uncertainty into multinational companies' tax departments as they plan for the 2026 tax year and beyond.

As part of an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development project, a collection of more than 130 countries successfully negotiated in 2021 model rules to combat tax avoidance consisting of two pillars. Pillar 1 aims to change where multinationals pay tax and Pillar 2 establishes a global minimum tax of 15% for companies with annual revenue of more than €750 million (approximately USD $873 million).

The Trump administration opposes Pillar 2, arguing that existing U.S. tax policies already establish a fair global minimum tax for U.S. firms. The Group of Seven nations want tax jurisdictions, namely countries who comply with the Pillar 2 standard, to agree to a "side-by-side system" that exempts U.S. companies from the proposed 15% global minimum tax. The Treasury Department has demanded that the countries agree to the exemption by Dec. 31, even though about 60 countries, including a majority of European Union nations, have already enacted Pillar 2 principles into their nation’s laws.

Double taxation threat looms

For U.S. multinational companies, no agreement means higher costs. "For taxpayers, if we don't get a deal it's going to mean onerous compliance requirements and double taxation. I think that's the bottom line," Cory Perry, Washington National Tax Office partner with the accounting firm Grant Thornton, said in an interview.

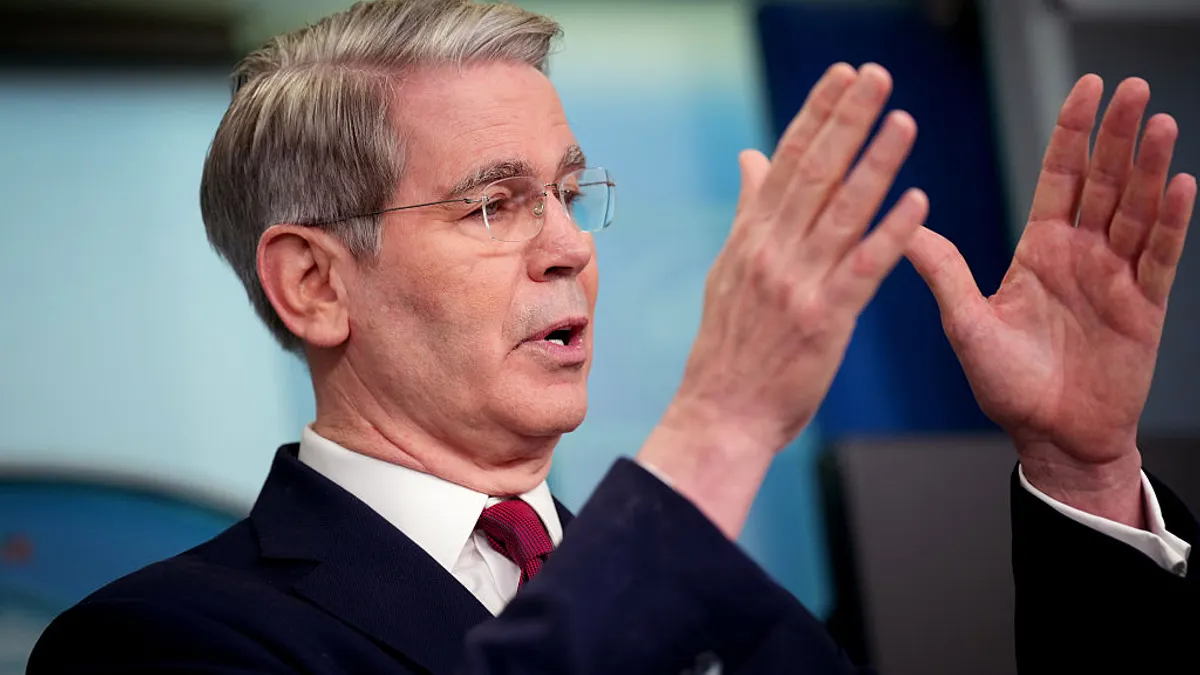

"This debate is about cooperation among countries versus the sovereignty of individual countries to set up their own tax systems as they wish. That's the theme of all of this: worldwide cooperation versus country sovereignty," Eric Solomon, a former Treasury Assistant Secretary for Tax Policy and now an Ivins Phillips Barker Chartered partner, said in an interview.

"Will the United States, negotiating with the OECD as well as the EU, find some arrangement under which a side-by-side system could be accepted? Who knows what's going to happen by December 31," Solomon said.

The OECD did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

No to Pillar 2

The global minimum tax was a key piece of the Biden administration’s plan to boost tax revenue to finance spending on infrastructure and improvements in U.S. competitiveness.

President Trump on the first day of his second term signaled a very different stance, ordering the U.S. to pull out of any agreements it had made with regard to what a Jan. 20 White House memorandum to Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent called a “global tax deal" and declaring Pillar 2 has no force or effect in the United States.

Treasury Deputy Assistant Secretary for International Tax Affairs Rebecca Burch reiterated that position on May 16. "We are not adopting Pillar 2. We are not moving towards Pillar 2," Burch said at a Tax Council Policy Institute conference, according to a transcript approved by conference speakers that was shared with CFO Dive.

The G7 countries, in the runup to the U.S. passage of the fiscal spending package named the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (Pub. L. No. 119-21), proposed a "side-by-side system" that acknowledges global intangible low-taxed income rules (GILTI) as a robust minimum tax regime and therefore fully exempts U.S. parented groups from two key Pillar 2 principles known as the Undertaxed Profits Rule and Income Inclusion Rule.

The 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (Pub. L. No. 115-97) included the new GILTI rules, a minimum tax intended to combat the abusive practice of shifting income to low-tax jurisdictions. Originally set at 10.5%, the GILTI tax rate increases to 12.6% for tax years beginning after Dec. 31.

In her May 16 speech, Burch set a deadline of Dec. 31 for an agreement to exempt the United States from the 15% tax regime. "[A]t the end of this year, I need the side-by-side system to be enacted," she said.

The Treasury Department did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

“Not a happy situation”

Tax lawyers said it's likely the G7 and countries adopting Pillar 2 will agree to at least a high-level or principles-only agreement by Dec. 31 that will then have to be negotiated in more detail during 2026. They added, however, that U.S. companies should prepare to comply with Pillar 2 components that enter into force Jan. 1 in case no deal is reached.

"If a country has a law that says you have to file these types of returns and make these types of calculations, you have to advise clients that they should be preparing those forms and complying with those rules, even if you think the rules are going to be adjusted, changed, appealed, or delayed," John Harrington, the co-leader of the law firm Dentons' U.S. tax practice, said in an interview

"You just don't know when or what kinds of transition rules will be put in place, or who's caught on the wrong side of them. So it's not a happy situation for anyone," Harrington said. Ongoing trade and tariff talks involving the United States only complicate matters, he said.

Grant Thornton’s Perry agrees that companies are facing a challenging situation. "I mean, we don't have a deal. We haven't seen a deal. Countries are releasing forms. The laws are on the books and legislated, and companies are required to file returns as soon as June of 2026 if not earlier in many jurisdictions," Perry said.

"Due dates are coming and if a deal is reached, that's great. But if you're a large multinational and you have to file in 50 jurisdictions, that's not something that's going to happen overnight, so you need to be prepared," Perry said.

Any deal may still trigger additional reporting requirements for 2025 and 2026, Perry said, and thos costs alone could run into the six or even seven digits.

AICPA seeks guidance

In a Sept. 4, 2025, comment letter the Association of International Certified Professional Accountants and Chartered Institute of Management Accountants asked the OECD and the Treasury Department to issue "comprehensive, harmonized guidance to ensure clarity, facilitate compliance, and minimize unnecessary administrative and reporting costs" for U.S. based multinationals.

Under Pillar 2 companies must calculate their effective tax rate for each jurisdiction where they operate and pay a top-up tax for any difference between their effective tax rate and the 15% minimum rate.

Countries around the world are now implementing the Pillar 2 regime. At least 22 of the 27 European Union countries have adopted in national law at least part of the Pillar 2 principles in accordance with an EU directive, according to a Tax Foundation analysis. And at least 60 counties in total have adopted at least some domestic legislation to comply with Pillar 2, Perry and others said.

Safe Harbor?

Despite, or perhaps because of, what's at stake Perry and others said they're optimistic some sort of deal will be reached by the year-end deadline. "We're getting very close to the finish line now, but it does seem like an agreement is within reach by the end of this year. I mean, that's what it sounds like," Perry said.

Others agreed. "I think the use of a safe harbor is probably the way this is going to play out," James Lawson, managing director of the public accounting firm Baker Tilly US said in an interview. Such a safe harbor could prevent Pillar 2 tax treatment from being imposed on U.S. companies until the details of how a side-by-side system would work are completed, he said.

A safe harbor would also mean the European Union won't have to remove an existing directive and enact a new one, which could take time and effort, Perry said.

Solomon said he's advising clients to closely monitor negotiations and consider what their tax obligations could be under various scenarios.

Revenge tax

If the Treasury Department doesn't act, Congress could. Language imposing additional taxes on companies domiciled in countries adopting Pillar 2 in ways deemed "unfair" to the United States was contained in a House-approved version of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act as Section 899. But the section was stripped out in the final version of the legislation approved by both the House and Senate and after the G7's call for a side-by-side system. Congress could re-introduce and approve the section to retaliate against Pillar 2 countries, tax lawyers said.

"The Republican-controlled House and Senate aren't enamored by Pillar 2," and legislators could enact the Section 899 text or something similar to it if no agreement is reached, Lawson said.

"Section 899 is not the law but it's hanging out there. If nothing gets resolved, if the side-by-side system agreement isn't reached, then Section 899 might be brought back by Congress if other countries impose taxes on U.S. companies," Solomon said.

"I don't want to speculate, but the Republicans have been quite clear in their own words that they will bring back this retaliatory measure if we don't reach a deal, and I have no reason to doubt they won't do that," Perry said.